It has been too long since my last post, what with life and all. I have so many delicious whiskey posts planned but with so few Spock mind-meld techniques at my disposal, I must submit to the available hours and the speed of my fingers.

It has been too long since my last post, what with life and all. I have so many delicious whiskey posts planned but with so few Spock mind-meld techniques at my disposal, I must submit to the available hours and the speed of my fingers.

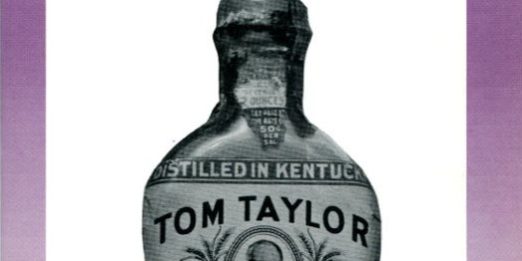

I’ve been blessed to have been born into whiskey royalty. My father, David M. Spaid, and his (and my) very good friend Harry A. Ford, Jr. put together a not-so-small effort to share some of the rarest miniature whiskey bottles known. Not content to make it 99 bottles, as the song goes, they made it 101. 101 Rare Whiskey Flasks. So rare, I don’t own any of them.

Believe it or not, there are a few copies of these 48-page booklets hanging out in the bowels of my father’s garage. You can still buy one for $10 including shipping if you want one. Printed in 1989 in black and white (color was crazy expensive back then for the short run they did) 101 Rare Whiskey Flasks will curl your toes and grow hair on your chest when you see the various rare brands and their designs.

With permission from the authors, I present to you the Introduction to 101 Rare Whiskey Flasks.

Scott Spaid

Editor, WhiskeyBent.net

101 Rare Whiskey Flasks – SOLD OUT

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to the world of miniature whiskeys. That’s whiskey with an “e”. The majority of people who have this book will use it as a guide and are already converted to the bottle collecting “faith”. For those of you whom this is your first look at miniature whiskeys, you’ll see many which would be considered the “best of show”.

There are a good many questions which collectors might have about this book. Some of these will deal with pricing, some with why certain bottles were chosen and others were not, and finally, why the era of the 1930’s and flasks or flats instead of just any style bottle.

To begin, let’s look at the title of the book, 101 Rare Whiskey Flasks. Not exactly snappy, but it does get the point across. There are 101 bottles here because it seemed to be a nice number, not overwhelming but more than a small sample. 101 also seemed to be important because the two of us could each show 50 of our favorite bottles and naturally one which both of us have in our collections.

The idea of flasks and the 1930’s sort of go together. Probably most collectors would easily agree that the 1930’s were the golden age for miniature liquor bottles and miniature whiskeys in particular. And, the best of these bottles were the flasks. Flats or flasks are very seldom seen today and that makes the older ones more interesting. After the ’30’s, we had the 1950’s and these were the war years… thus a great many brands went to the wayside. The 1950’s saw the beginning of the taste changes in the American public which has resulted in the “white goods” epidemic. (White goods are clear spirits such as vodka, rum, and gin.) The 1960’s saw economics take over so that fewer and fewer brand names were produced. After all why should a company distribute 20 brands and take the time and expense to make up new labels when all the same liquor could easily be sold under just one brand name.

The thirties were something special though. With the end of prohibition in December of 1933, everyone who could begin producing whiskey. After all, the nation had seen well over a decade of bathtub gin, Canadian whiskey, and the best (or worst) Scotland had to offer. It was time to get down to old bourbon and rye…American drinks! No one knew what would really catch on. It might be the taste or maybe it would be the name of the whiskey or even the label design. Demographics weren’t a big thing in the mid-1930’s. So if you could produce bourbon or even buy it from someone who did produce it and had the necessary licenses, you could begin issuing any whiskey you wanted to. If your Aunt Fanny had a taste for the strong stuff, why not take that one-month-old “stuff” and call it Aunt Fanny’s blend!

Liquor stores got in the act too. You’ll notice several bottles in this book, which were made for specific stores or a chain of stores. Most whiskey was produced in Kentucky, Indiana, Maryland, and Pennsylvania but it could easily be trucked anywhere and bottled there. California was a prime example. Take a gander at the bottoms of those labels and you’ll note that a good number of them were produced here in the Golden State.

Most collectors realize that the same exact whiskey goes into a number of different bottles and many companies filled for a variety of other companies. Few people though realize how prevalent this still is. Ever notice that Jim Beam has bottles which state they are bottles by James B. Beam? Ever wondered if there is a Wild Turkey distillery? (There isn’t.) So, it was in the 1930’s that the same liquor might have gone into a score or more of different brand names. Thus the Hinze people in Kentucky could produce both War Admiral and Frederick. Are we really to think these were two different whiskeys? It’s possible but highly improbable. Consequently, the 1930’s had literally hundreds of different brand name whiskeys.

This leads us to the point that if there were hundreds of miniature brand names produced, why did we pick these particular ones. The answer to this question has several parts.

Rarity is one of the reasons. Availability is another. These sound almost alike, but they really aren’t. It is always wonderful to see rare bottles you’ve never seen before; however, it is extremely frustrating to be unable to ever add them to your collection.

A good many California bottles were picked because of their rarity. Quickee’s Fernwood (a name we feel which definitely deserves notation) along with the Wilshire Midget and the others are in the “knock your socks off” category. We did not include such bottles as Green Mill and Old Cask because they have previously been shown in other books. We carefully gleaned the contents of the six books (Snyder, Triffon, Spaid) done in the last two decades so that nothing shown in those pages would have been seen in another book. A few of the bottles here have presented in a club newsletter or two; however, for the most part, everything in these pages is pictured here for the first time!!

Now we come to what may be the most controversial aspect of the book, the pricing. Pricing a bottle is a no-win situation. As soon as the price appears, the value either goes up or down. The swap meet sellers and antique dealers who really care nothing about the bottles per se will begin smacking their lips because now they can point to a book a say, “See, there’s the value, right there!” The collector moans and groans because he or she wants more bottles but doesn’t want to pay the price. No one ever remembers that the value of his own collection has just gone up if he owns any of the pictured bottles.

If you’re wondering how we came up with these prices, that answer is simple. The old law of supply and demand is the answer. Look to the bottles which are sold either at the shows or directly from collections. Read every copy of each and every auction magazine which has ever been published. Last year (editors note: this would have been 1987 or 1988) when Old Camel (Triffon, Volume 1) went for $500 in the Mini Bottle International auction everyone was amazed. But where can you get an Old Camel bottle?

Now here’s a WARNING. Don’t start thinking that every whiskey miniature from the 1930’s is worth a humungous price. It isn’t. There just might be one hundred thousand Mill Farm bottles floating around. Great looking label in perfect condition … maybe it will bring $10, possibly $12. Now Four Bits, that’s a different matter. We know of exactly four of them. So, it’s supply and demand. In fact, the majority of whiskey bottles from the ’30’s would sell for $20 or less. Gins, rums, and cognacs would generally fetch even less. And liqueurs, brandies, and wines will usually be under $5.

So, if you like the prices great. If you don’t like the prices, then buy, sell and swap the bottles for what you think they are worth. We happen to think the bottles in this book are worth a great deal. And, incidentally, just in case you’re considering asking us … we’re not selling … and we’re not trading.

Let us know what you think of this book, and whether you’d like to see more in the future. Finally, good bottle hunting!

— David M. Spaid & Harry A Ford, Jr.